Updated July 24, 2021

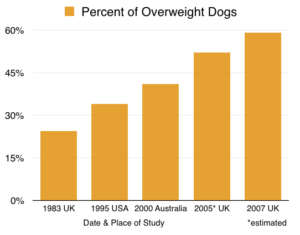

If we assume that the US, UK and Australia have similar dog cultures then we’re watching a slow train wreck.

Does it really matter? Aren’t vets just a little too obsessed by your dog’s weight?

Overweight Dogs: The Evidence

Overweight dogs are more likely to:

- Die an average of two years earlier

- Have poorer quality of life

- Have arthritis

- Rupture a cruciate ligament

- Get cancers

- Have lower urinary tract disease

- Have oral disease

- Be less active

So let’s assume that no one wants to knowingly let their dog get too fat. This is where it gets controversial: exactly what an overweight dog is depends on who is looking.

- Breed standards often ‘normalise’ an overweight state despite vets’ disapproval. A 2015 study of Crufts dog show found that 26% of dogs placing first to fifth were overweight. That included 80% of pugs, 68% of Basset hounds, and 63% of Labradors.

- I’ve previously talked about how owners of dogs at their ideal weight often get singled out by dog park busybodies for underfeeding their dog. That’s because fat dogs are now seen as the ‘normal’.

- Owners don’t always see what vets see. It has been demonstrated that the difference in perception gets worse the bigger the dog gets.

We usually define an overweight dog as having a body weight 15% above their ideal. The problem is that dog weight guides don’t account for different sizes of dogs. It’s best judged by giving a body condition score, not an arbitrary number of kilograms.

Risk Factors For Obesity

What is the evidence for which dogs are more likely to get overweight?

Breed

Certain breeds are known to be more at risk. You need to be especially careful with Retrievers, non-Australian working dogs, Cocker Spaniels, Dalmatians, Dachshunds, Rottweilers, Shetland Sheepdogs and mixed breeds.

Age

It’s no surprise that the older a dog is, the more likely they will be overweight. After 10 it reverses, probably due to the influence of disease.

Sex

In order of risk from high to low it’s:

- Desexed females

- Desexed males

- Entire females

- Entire males

I’ve said it before: despite the clear health benefits of desexing, if you don’t think you can keep your male dog lean, he’s better off not neutered. Females are probably better desexed regardless.

Exercise

This could be a whole article in itself. There are many benefits of dog walking but no evidence of any effect on weight.

Two studies (one using accelerometers!) found that only vigorous activity was associated with better weights, but that isn’t an option for most dogs. It can even be positively harmful, especially in overweight animals.

How Often Fed

As the number of meals increase, so too does weight. It’s easy to guess why: it’s very hard to keep the meal size small enough once they get split up.

Disease

Hyperadrenocorticism and hypothyroidism are a couple of hormonal diseases that can cause obesity. There are also several adverse effects of medications that can do the same thing.

Culture

This part there’s no evidence for, but (pardon the pun) it’s the elephant in the room. The rise in overweight dogs has gone hand in hand with our dogs coming inside and becoming family members. It’s also coincided with the emergence of a huge pet food industry, where the best profit margins aren’t on good foods, they’re on treats. I wonder how many people are told their dogs don’t need that treat you bought.

Now read our guide to helping a dog lose weight which is 100% judgement-free and based on 25 years of helping dog owners like yourself.

Have something to add? Comments (if open) will appear within 24 hours.

By Andrew Spanner BVSc(Hons) MVetStud, a vet in Adelaide, Australia. Meet his team here.

Further Reading

Information for this article came from these papers, many of which can be read in full via Google scholar.

Colliard, L., Ancel, J., Benet, J. J., Paragon, B. M., & Blanchard, G. (2006). Risk factors for obesity in dogs in France. The Journal of nutrition, 136(7), 1951S-1954S.

Courcier, E. A., Thomson, R. M., Mellor, D. J., & Yam, P. S. (2010). An epidemiological study of environmental factors associated with canine obesity. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 51(7), 362-367.

Edney, A. T., & Smith, P. M. (1986). Study of obesity in dogs visiting veterinary practices in the United Kingdom. The Veterinary Record, 118(14), 391-396.

German, A. J., Holden, S. L., Wiseman-Orr, M. L., Reid, J., Nolan, A. M., Biourge, V., … & Scott, E. M. (2012). Quality of life is reduced in obese dogs but improves after successful weight loss. The Veterinary Journal, 192(3), 428-434.

Holmes, K. L., Morris, P. J., Abdulla, Z., Hackett, R., & Rawlings, J. M. (2007). Risk factors associated with excess body weight in dogs in the UK. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 91(3‐4), 166-167.

Kealy, R. D., Lawler, D. F., Ballam, J. M., Mantz, S. L., Biery, D. N., Greeley, E. H., … & Stowe, H. D. (2002). Effects of diet restriction on life span and age-related changes in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 220(9), 1315-1320.

Lund, E. M., Armstrong, P. J., Kirk, C. A., & Klausner, J. S. (2006). Prevalence and risk factors for obesity in adult dogs from private US veterinary practices. International Journal of Applied Research in Veterinary Medicine, 4(2), 177.

Morrison, R., Penpraze, V., Beber, A., Reilly, J. J., & Yam, P. S. (2013). Associations between obesity and physical activity in dogs: a preliminary investigation. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 54(11), 570-574.

McGreevy, P. D., Thomson, P. C., Pride, C., Fawcett, A., Grassi, T., & Jones, B. (2005). Prevalence of obesity in dogs examined by Australian veterinary practices and the risk factors involved. Veterinary Record-English Edition, 156(22), 695-701.

Such, Z. R., & German, A. J. (2015). Best in show but not best shape: a photographic assessment of show dog body condition. The Veterinary record, 177(5), 125-125.